The laws of robots are chiefly referred to as laws of human-robot relations. These laws have the founding roots in the design and implementation of industrial robots.

Three Laws of Robotics

The present article discusses three laws of robotics proposed by the science fiction writer Isaac Asimov. According to Asimov, the three laws of robotics are stated below:

First Law

A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

Second Law

A robot must obey the commands given by human beings unless they conflict with the first law.

Third Law

A robot must protect itself against harm unless that conflicts with the first and second laws.

The algorithmic link to which the three laws of robotics are knitted seems to be relentless at first sight, yet they do not cover all the practical scenarios.

If the designed robots do not harm humans, what if humans harm other human beings?

This philosophical insight led Adimov to develop the Zeroth Law, which was expounded in his fictive stories by the robot R. Giskard Reventlov.

The Zeroth law of robotics thus states:

A robot must not harm humanity or, through inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.

It is evident by the close reading of the Zeroth and the first law that the difference between the two statements is that of a human being and humanity. It implies that the Zeroth law places humanity above the individual. But, by this, do all the conflicts stand resolved?

All problems solved? Every dreadlock unentangled? The explicit answer is “no.” What if the robot is not a robot in the first place by changing (morphing) into a replicant that is designed with human DNA or genomic elements?

What about military killer robots who, based on ethical judgment, shoot bad guys to save the good ones? The pertinent question among many others that comes to mind is: what should be the minimum IQ of a robot?

Leaving these key moral questions to the philosophers or transhumanists such as Rosi Braidotti, Donna Haraway, and others to answer, let’s steer the discussion to its pragmatics through a concise analysis.

Analysis

Asimov’s three laws of robotics fundamentally consist of two characteristic elements. These two are as follows:

- Robot’s ability to judge in case of the infringement or the invocation of any robotic law, and analyze the situation for any action and inaction.

- Robot’s ability to take any action whatsoever to comply with the stated robot laws.

Of the two elements, the first one appears more daunting and challenging as it requires complex decision-making.

Are Asimov’s laws implementable?

These three laws are somewhat problematic to the robot designers as they feel that these laws threaten their autonomy.

Upon close reading, one can evaluate these laws as a consequence of ethical obligation to workplace organization, and human safety from the vantage of robotization and automation of industrial operations.

Due to their great influence, these laws have provided a central pivot for the ethical fulcrum of future AI machines to work in and behave responsibly in human societies.

In truth, Asimov’s laws are not implemented as such as the robots for which these laws are formulated do have very limited semantic abilities. What the robots can do is efficiently run the pre-feed instructions in a well-structured coded language.

However, there are a few exceptions that are surfacing nowadays in the form of deep learning (DL) as implemented by IBM in its Watson machine. Such machines show that they have shared interests with human beings.

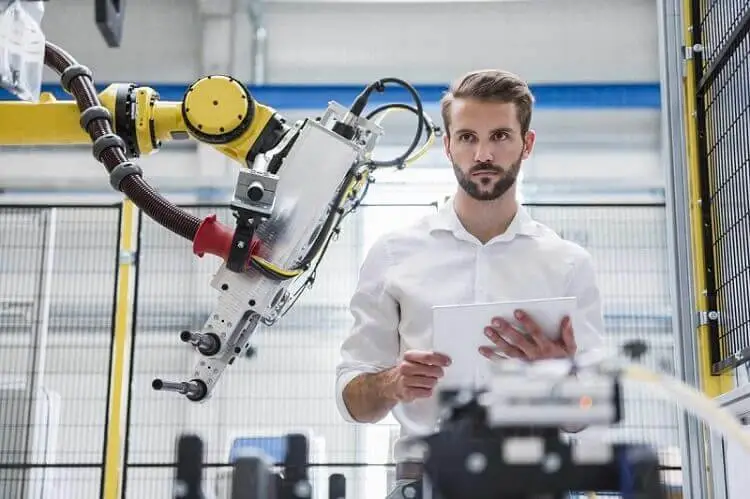

It is a commonplace practice at present that we witness robots co-working with machine operators in factories without harming or hurting human beings.

They are made to feel the presence of a human being and be cautious when they enter the proximity circle: by controlling the movements of their body, they are becoming a part of a new army of (robot-)labor and, therefore, are collectively deemed human-friendly.

Yokomizo Seven Rules of Robots

Over time, there has been a lot of critical debate over the various modalities of Asimov’s laws. Until recently, a set of new rules was framed by Yokomizo et al. in 1987.

These rules have gained comfortable acceptance among robotic communities and scientific circles. We reproduce these seven rules as under:

Rule 1: Robots must be constructed and used for the well-being and development of the people.

Rule 2: Robots must not replace people in jobs who want to keep their jobs. They, however, must replace those who want to quit their jobs or consider their work hazardous.

Rule 3: Robots must be built to such specifications that they would not psychologically or physically oppress people.

Rule 4: Robots must follow the commands of people so that they do not harm other people yet may harm themselves.

Rule 5: If robots are to replace people, the prior consent of those affected would be sought.

Rule 6: Robots must be interfaced in such a way that the worker can easily operate them and can readily perform the duties of assistance.

Rule 7: As soon as their designated tasks are completed, they must depart from the workspace to not interfere with humans and other robots.

These rules have certain positive and negative implications for the human workers. The effect of the use of robots in the workplace can thus be summarized as follows:

- Rise in the risk and occupational hazard at the place of work

- Loss of jobs

- Decline in wages

- Job content

- Environmental hurdles

- Mental stress and physical pain

- Educational issues

- Distorted social behaviors

Frequently Asked Questions

What are Asimov’s three laws of robotics?

Asimov’s three laws of robotics state that: 1) a robot must not harm a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm; 2) a robot must obey the commands given by the human being unless they conflict with the first law; 3) a robot must protect itself against any harm unless it conflicts with the first and the second law.

Is there any fourth law of robotics?

Yes! It is called Asimov’s fourth law of robotics. It states that a robot may not harm humanity or, through inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.

I am the author of Mechanical Mentor. Graduated in mechanical engineering from University of Engineering and Technology (UET), I currently hold a senior position in one of the largest manufacturers of home appliances in the country: Pak Elektron Limited (PEL).